As bad as this pandemic is, and as bad as the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic was, there was an epidemic you probably have never heard of that almost brought the economy to its knees. You wouldn’t be aware because it didn’t affect people. Its victims were horses.

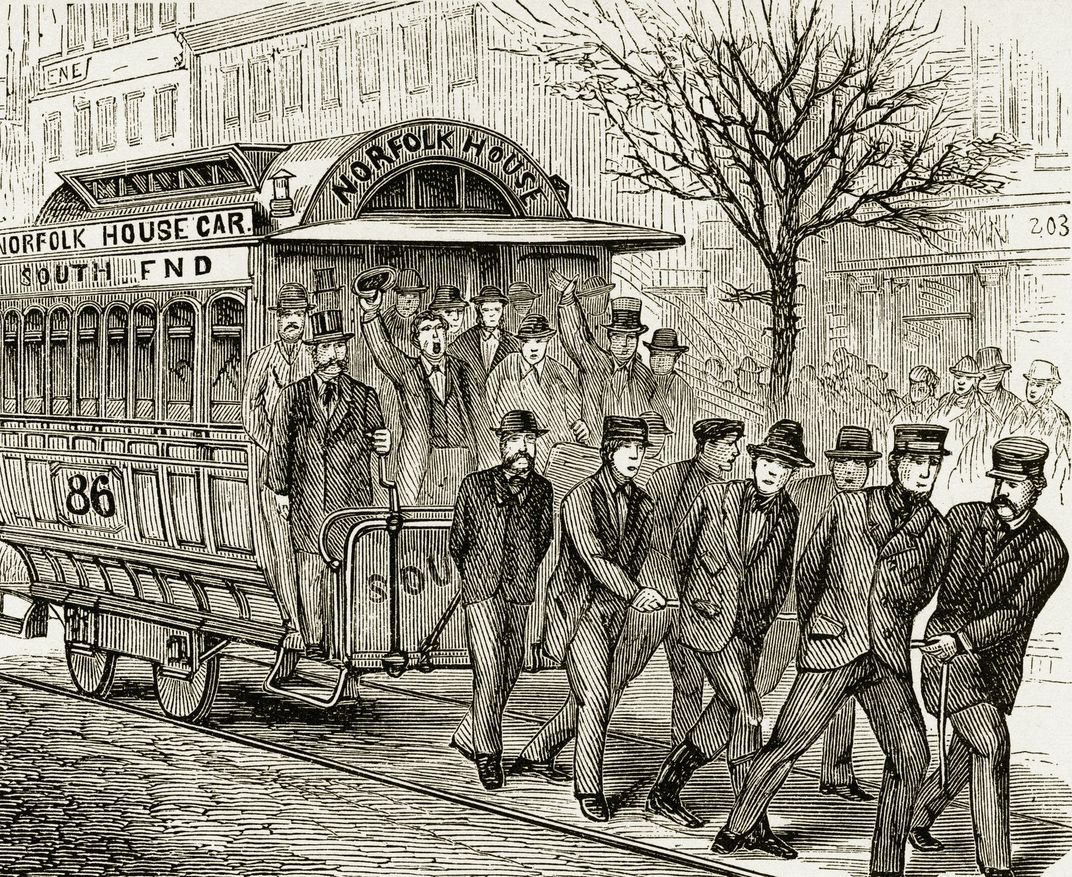

So why was this so serious? It came at a time that our local transportation was based on these four-legged beasts.

The year was 1872. Remember the germ theory of disease was still controversial, and viruses would not be identified for another 20 years. Health options were limited to disinfecting stables, improving animal feed, using new blankets, and whatever home remedies might be thought to work. So when equine influenza first appeared in late September outside of Toronto, Canada, the disease spread quickly. Most animals in the city’s crowded stables were ill within days. The U.S. government moved to ban Canadian horses, but it was too late. Within a month border towns were infected, and the “Canadian horse disease” quickly spread across the country.

It was undeniably influenza: a rasping cough and fever, drooping ears, and loss of energy. By one estimate, two percent of an estimated 8 million horses in North America died as a result. And as in the current human pandemic, many more animals suffered symptoms that took weeks to clear.

The economic effects were far-reaching. Horses were too sick to transport coal out of mines, sending fuel prices climbing. Crops couldn’t get to market, nor could raw materials make it to factories. There were no beer deliveries to saloons. Postmen were reduced to using wheelbarrows. Travel became much more difficult. The economy plunged into a steep recession.

Perhaps worst of all, firemen could no longer rely on horses to pull their heavy pump wagons. On November 9, 1872, a catastrophic blaze gutted much of downtown Boston when firefighters had to respond on foot.

The situation was exacerbated when desperate or callous owners forced their animals to work despite being ill, which often proved fatal. E.L. Godkin, the editor of The Nation, called such treatment “a disgrace to civilization … worthy of the dark ages.”

One positive development was the disease publicized the need for better treatment of all animals. The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals had been founded by Henry Bergh in 1866. Seeing an opportunity in this epidemic, Bergh used inherited wealth, connections and literary talents to lobby New York’s legislature to pass the first modern anti-cruelty statute. Bergh and his agents used the police powers granted by this new law to patrol the streets of New York City to defend animals from avoidable suffering.

Just like today, many wondered if the world they knew would ever recover. Eventually, the disease ran its course and life gradually returned to normal.

But the crisis also caused a much-needed examination of the treatment of animals. I’m sure a similar examination of our pre-pandemic routines will also happen eventually. Like in 1872, the effects on our lives is profound, but we will end up being stronger for it.

Taken from “The Horse Flu Epidemic That Brought 19th-Century America to a Stop” by Ernest Freeberg (https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-horse-flu-epidemic-brought-19th-century-america-stop-180976453/?).

To read more about Henry Bergh, see A Traitor to His Species: Henry Bergh and the Birth of the Animal Rights Movement by Ernest Freeberg.