I will admit that being both a regular user of Facebook and a history nerd, plus having a policy of not unfriending anyone, does bring some excitement into one’s life. As such, I have been avidly following the discussions about Black Lives Matter, especially the counterargument that all lives matter.

Yes, all lives certainly should. But I think the point is they never have, beginning with the U.S. Constitution’s proclaiming a slave counting as three-fifths of a person (Article I, Section 2, Clause 3). Still, in the 21st Century, it’s hard to imagine what race relations have been like at their worst, especially if you’ve been born after about 1980. To recall exactly how bad race relations have been, I’ve been doing a bit of research. For what it’s worth, here are some facts about events you might not have been aware of. Call it a reminder of the sanctity of human life.

Library of Congress

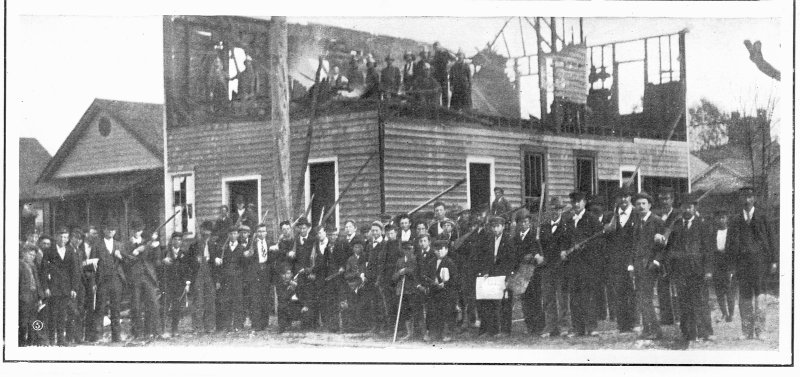

Wilmington Massacre and Coup (1898) — Brutality against freed slaves began in Wilmington, North Carolina as soon as the Civil War ended, thanks to a former Confederate general as police chief and an all-white police force. The most extreme example occurred in 1898, with what can best be described as a coup that overthrew a legitimate multi-racial government in the South’s most progressive Black-majority city. At least 60 Black men were murdered and leading Blacks (and any white political allies) were forcibly removed from office. In the following weeks, more than 2,100 African-Americans fled the city, turning it from black-majority into a white supremacist stronghold.

As a result, Black voter registration in North Carolina went from 126,000 two years before the coup to 6,100 four years after, no Black citizen again served in public office in Wilmington until 1972, and no Black citizen from North Carolina was elected to Congress until 1992. By the way, there were no prosecutions for these crimes.

For more, see “The 1898 Wilmington Massacre Is an Essential Lesson in How State Violence Has Targeted Black Americans” by David Zucchino (https://time.com/5861644/1898-wilmington-massacre-essential-lesson-state-violence/)

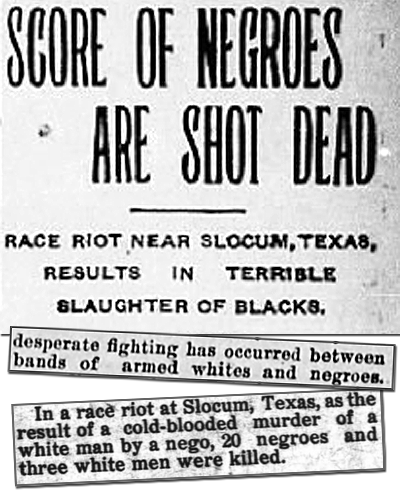

Slocum, Texas Massacre (1910) — In the early 20th Century, Slocum was a mostly African American unincorporated community with several prosperous Black citizens. White agitators began warning of plans for a race war, and on July 29, white mobs from all over Anderson County started acting on their fears, aided by initial newspaper reports portrayed Blacks as armed instigators. “Men were going about killing Negroes as fast as they could find them,” Sheriff William H. Black told the New York Times. “These Negroes have done no wrong that I can discover,” Black continued. “I don’t know how many were in the mob, but there may have been 200 or 300. They hunted the Negroes down like sheep.” Officially, between eight and 22 African Americans were killed, but the real toll was probably 10 times that number.

Taken from https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/slocum-massacre/.

East St. Louis Race War (1917) — During World War I, Blacks moved from the South to East St. Louis to work in factories supporting the war effort; the Black population nearly doubled between 1910 and 1917. In the spring of 1917, the mostly white workforce at the Aluminum Ore Company went on strike and was replaced with Blacks. The racial tensions exploded from July 1st to 3rd, 1917 when white mobs started beating any African Americans they found. Many tried to escape by crossing the Mississippi River, but the police closed the bridge, leading to an unknown number of drowning deaths. According to one witness, “My uncles said they had to stay on the Missouri side of the river, and in the east the horizon was just glowing for weeks from burning buildings. For days afterward, you could still hear screams and gunshots.” The official toll was 39 Black individuals and nine whites dead, but many believe that more than 100 Blacks were killed.

Taken From “The East St. Louis Race Riot Left Dozens Dead, Devastating a Community on the Rise” by Allison Keyes (https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/east-st-louis-race-riot-left-dozens-dead-devastating-community-on-the-rise-180963885/).

Elaine Massacre (1919) — Sharecropping is a tough way to make a living. Yet when Black sharecroppers and tenant farmers in Phillips County in the Arkansas Delta tried to challenge the system, all they got was death and destruction.

The small town of Elaine had ten times as many black residents as white. So when word got out that Blacks were joining a union called the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America, whites felt threatened. A confrontation September 30 led to a gunfight, and a white posse of between 600 and a thousand men, some from out of state, was organized. That led to the arrival of 600 federal troops, who were told “negro insurrectionists” were “killing the whites whenever they ventured out to their farms,” which led to the order to “kill any negro who refuses to surrender immediately.” This translated into orders “to shoot everything that showed up,” which resulted in bragging about “shooting them down like rabbits.” The final death toll is unknown, but it had to have been over a hundred.

From “The Ghosts of Elaine, Arkansas, 1919” by Jerome Karabel (https://getpocket.com/explore/item/the-ghosts-of-elaine-arkansas-1919).

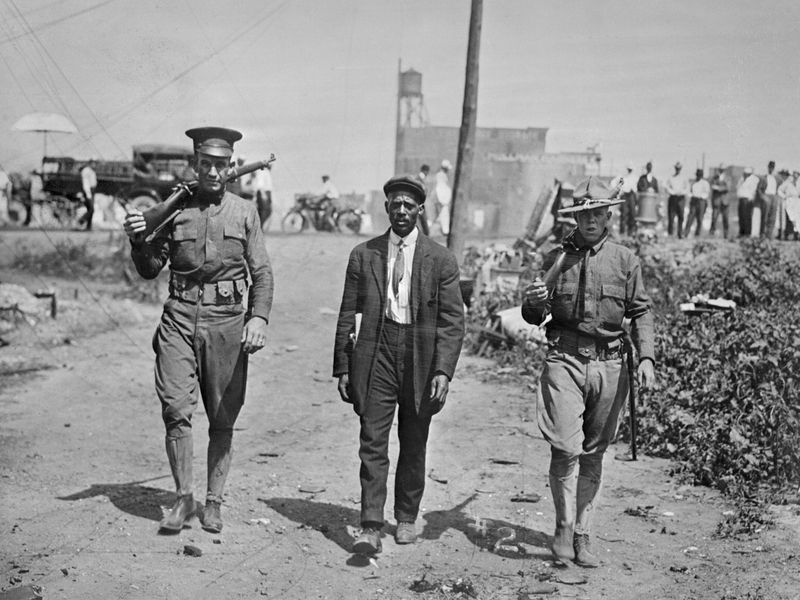

Tulsa Race Massacre (1921) — By now, everyone should know what happened in Tulsa in 1921, although I have never found an account in a history book. The Greenwood District was so prosperous it was nicknamed the “Black Wall Street,” thanks to the region’s oil boom. Then rumors of an elevator altercation between a black man and a white woman on May 30 led to a white mob looting and burning the district. Airplanes dropped turpentine bombs, the first documented instance of a U.S. city suffering aerial bombardment. Martial law was declared and the National Guard was brought in to restore order. At least 6,000 African Americans were interned by the National Guard for as long as eight days at the Convention Hall and Fairgrounds. Thirty-five city blocks were destroyed; the aftermath resembled Hiroshima, Japan after the 1945 atomic bomb attack. The death toll was estimated to be at least 300.

For more information, see https://www.tulsahistory.org/exhibit/1921-tulsa-race-massacre/#flexible-content and https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/factcheck/2020/06/17/fact-check-tulsa-race-massacre-worst-u-s-riot-isnt-ignored-history-books/5341812002/.

Rosewood, FL Massacre (1923) — On New Year’s Day, 1923, a white woman from Sumner, FL was beaten. She claimed her assailant was black and, although she didn’t have a name, the sheriff came up with one, Jesse Hunter, and the posse went looking for him in Rosewood. They didn’t find him, but they noticed how prosperous the little community was, and in seven days of violence the town was wiped off the map. “They didn’t find Jesse Hunter, but noticed that here’s a bunch of niggers living better than us white folks. That disturbed these people,” said one witness. All buildings were systematically burned. According to the Gainesvile Sun, “The burning of the houses was carried out deliberately and although the crowd was present all the time, no one could be found who would say he saw the houses fired.”

Despite widespread coverage at the time, the state did nothing and the entire episode was forgotten until 1982, when a reporter at the then St Petersburg Times resurrected the story. This led to something very unusual — the Florida Legislature voted victims’ compensation of $2.1 million in April, 1994.

Taken from “Rosewood Massacre a Harrowing Tale of Racism and the Road Toward Reparations” by Jessica Glenza (https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/jan/03/rosewood-florida-massacre-racial-violence-reparations).

How many of these were you aware of?

Finally, a personal note. Several years ago, I visited Montpelier, VA, the estate of James Madison, our fourth president. It’s operated by the Montpelier Foundation as “A memorial to James Madison and the Enslaved Community, a museum of American history, and a center for constitutional education that engages the public with the enduring legacy of Madison’s most powerful idea: government by the people” (https://www.montpelier.org/).

It’s always fun to visit these sites; they’re a real insight into history. And since Madison was a slaveholder, the “Enslaved Community” is a big part of the story, too. What I remember most from my visit was the contrast between the Madison Family Cemetery, the final resting place for James and Dolley Madison with the requisite monuments and headstones, and the Slave Cemetery — “Here graves are marked by depressions in the ground and an occasional quartz headstone.” It looked like an empty field to me.